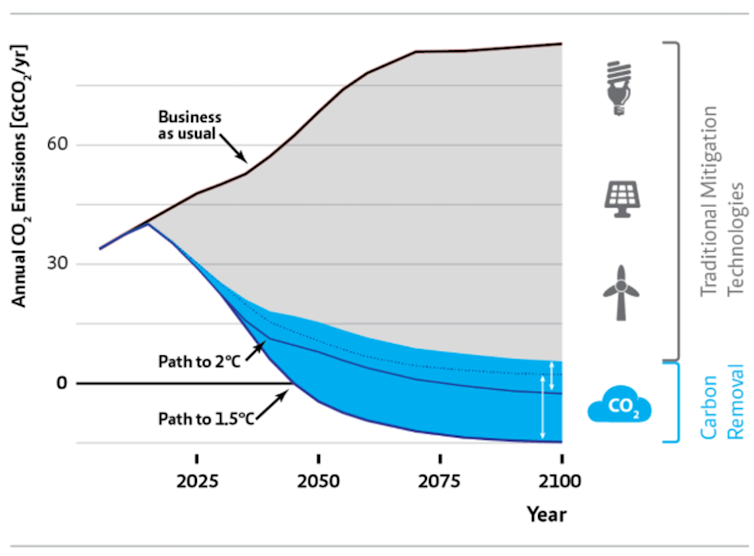

Many scientists believe that halting global warming at 1.5°C will require us to invent Negative Emission Technologies – machines that can suck climate warming gases like carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the air. But such technology already exists and has done for over two billion years. From the trees outside your window to the microscopic algae in the ocean, nature is working hard to absorb the atmospheric carbon that is heating our world.

Rather than reinvent the wheel, some experts are calling for natural solutions to climate change. These involve restoring natural habitats – such as forests and wetlands – which would draw down CO₂ through photosynthesis and store it as living tissue in plants.

Rapidly phasing out greenhouse gas emissions is still vital, but letting nature do much of the hard work in removing the CO₂ that’s already in the atmosphere could save the time and money we’d need to develop artificial methods of capturing carbon.

Read more: George Monbiot Q + A – How rejuvenating nature could help fight climate change

Returning many of the world’s ecosystems to something resembling their former glory could also help solve another crisis simultaneously. In this fourth issue of the Imagine newsletter, we look at the mass extinction crisis that threatens the nearly nine million species on Earth and how radical action to prevent their extinction could also prevent ours.

We asked experts to imagine how natural solutions to climate change could start at home and what a future with more of the wild in our lives might look like. In the end, it’s a case of saving two birds with one tree.

What is Imagine?

Imagine is a newsletter from The Conversation that presents a vision of a world acting on climate change. Drawing on the collective wisdom of academics in fields from anthropology and zoology to technology and psychology, it investigates the many ways life on Earth could be made fairer and more fulfilling by taking radical action on climate change.

You are currently reading the web version of the newsletter. Here’s the more elegant email-optimised version subscribers receive. To get Imagine delivered straight to your inbox, subscribe now.

A wilder world is a cooler world

Nearly a million species are at risk of extinction without “transformative changes” to the way societies and economies are organised in the 21st century. That’s according to a report published in May 2019 by an international team studying Earth’s biodiversity.

Read more: ‘Revolutionary change’ needed to stop unprecedented global extinction crisis

Climate change drives species to extinction and exacerbates threats such as habitat loss, by destroying the habitats themselves or changing the conditions that make them hospitable to different species.

But it might surprise you to learn that across vast swathes of the world, nature is already returning to places where dense habitats were once destroyed by humans. Even on your own doorstep, your local environment could be wilder than it was 100 years ago.

If you live in mainland Europe, that’s almost certainly the case.

Read more: Rewilding: as farmland and villages are abandoned, forests, wolves and bears are returning to Europe

More and more people around the world are abandoning rural landscapes and moving to live in cities. In their absence, the land they once used for agriculture is regenerating as shrubland and forest. These new habitats have ushered in wolves, brown bears, lynx and boar. José M. Rey Benayas, Professor of Ecology at the University of Alcalá, says:

Despite 40% of the world’s land being cultivated or grazed permanently by domestic herbivores… forests returned at a rate of 2.2 million hectares per year between 2010-2015 alone. Spain, for example, has tripled its forest area since 1900 – increasing from 8% to 25% of its territory. The country gained 96,000 hectares of forest every year from 2000-2015.

In the UK, forests have recovered more slowly, from 5% of the land area after World War I to 13% today. It’s been estimated that every hectare of forest that’s restored in the UK could absorb the annual emissions of 30 London buses or 90 cars every year. Restoring forest cover in the UK to just 18% of the land area could absorb a quarter of the carbon that will need to be cut in order to reach net zero emissions by 2050.

Read more: Rewilding is essential to the UK’s commitment to zero carbon emission

Aside from not emitting carbon in the first place, restoring forests across the world on an unprecedented scale could be our best bet for avoiding catastrophic climate change, according to a new study. Mark Maslin, a Professor of Earth System Science and Simon Lewis, a Professor of Global Change, both at University College London, explain the thinking.

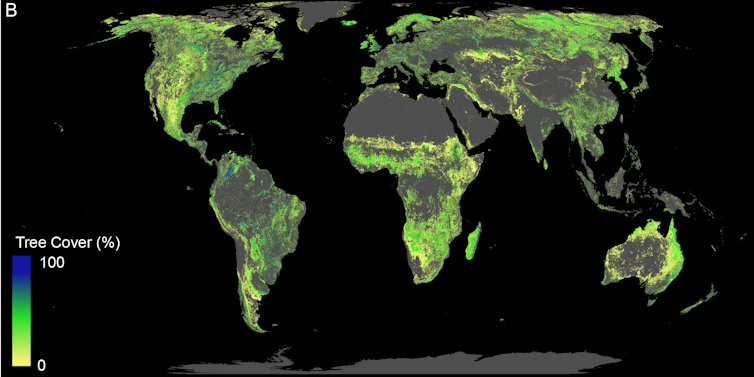

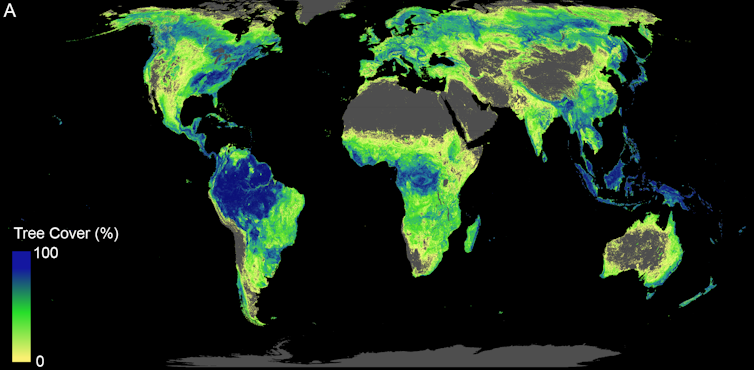

Negative emissions – Increasing the world’s forest land by one third – regrowing an extra billion hectares of trees over an area that’s roughly the size of the United States – could capture 205 billion tonnes of CO₂, according to the study. That’s about two thirds of man-made carbon emissions already in the atmosphere.

Low disruption – The study’s authors say reforestation on this scale could actually be achieved with fairly limited disruption to our lives. Most of the land needed would be around 1.8 billion hectares in areas with low human activity, so new forests wouldn’t have to compete with land we’d need to reserve for growing food.

But there’s a catch – Even if global warming is limited to 1.5°C, the higher temperatures could reduce the area that’s suitable for forest restoration by a fifth by 2050. On its own, reforestation isn’t enough. There’s still a very urgent need to reduce emissions drastically for a reasonable chance of avoiding catastrophic climate change. As Maslin and Lewis point out, the actual sum of CO₂ that reforestation could lock away is also much smaller in other research, perhaps closer to 57 billion tonnes.

Rewilding starts at home

Reforesting the Earth will take decades, but right now, people in the UK could help bring back one of the country’s most diminished habitats in their own backyards. Since the end of World War II, Britain has lost 97% of its wild grassland – turned into farmland or dug up to build roads and homes.

What’s left is a sorry sight. The clipped lawns and neat grass verges of Britain mostly contain only one or two species of turf grass, compared to the more than 40 plant species that can thrive in a single square metre of grassland. As their native habitat has declined, British pollinating insects have vanished from a third of their range since 1980.

Read more: Four steps to make your lawn a wildlife haven – from green desert to miniature rainforest

Maintaining the hyper-manicured lawns that we’re used to seeing in public parks often involves petrol mowers and fertilisers which leak more carbon to the atmosphere during their production and use than the grass itself can store.

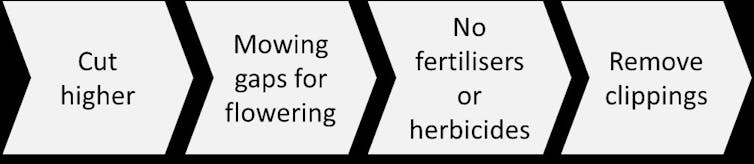

If you have a lawn, you can think of it as your own patch of artificial grassland – a stunted remnant of a once vast ecosystem. But it needn’t be that way, says Adam Bates – an ecologist at Nottingham Trent University. There are four easy steps any gardener can follow to turn their lawn into a wildlife haven that locks away CO₂.

1. Cut higher

Most lawn mowers have blades that are set as low to the ground as possible, ensuring that the lawn is cut to be flat and featureless, which is no good for wildlife. Bugs and small creatures need nooks and crannies to hide from predators. Spiders in particular need something to anchor their webs to.

By adjusting the blade to the highest possible setting – often around 4 cm off the ground – mowing can leave taller grass with more recesses for insects to hide in.

2. Include mowing gaps

Leaving longer gaps between mowing the lawn can give wildflower species the time they need to flower and provide nectar for pollinating insects to eat. By leaving a gap in spring, early flowering species like the native cowslip can bloom.

Cowslip is a plant which has been declining for decades, but the Duke of Burgundy butterfly depends on it for somewhere to lay its eggs.

Leaving a mowing gap in summer can give species like cat’s-ear and fox-and-cub time to flower – both important food sources for leafcutter bees.

3. Don’t use fertilisers or herbicides

You might expect herbicides to be a bad idea, but when it comes to lawns, fertilisers are only good for ensuring a luxuriant green colour – one or two grass species will soak up the extra nutrients and outcompete everything else.

To ensure a rich variety of plants can thrive in your wildflower lawn, reducing the fertility of the soil is essential.

4. Remove the clippings

By collecting the cut grass after you mow you can stop more nutrients getting into the soil and reduce the lawn’s fertility with every cut.

If you’re 100% committed, you can leave strips at the sides or patches in the corners to go wild and form small wildflower meadows. Most wildflower seeds will be carried to your garden on the wind or by birds, but if you’re tired of waiting, you can buy and spread the seeds yourself.

Once you’ve seen pockets of wildflower meadow spring up on your lawn, you may not want to stop there…

Ponds – the carbon sink in your backyard

Pollinator species would certainly benefit from more people turning their lawns into the wild grassland habitat that’s so rare in the British landscape today. But a single square metre of grassland might only absorb about 2-5g of CO₂ over the course of a year. So how helpful is rewilding your garden for slowing climate change? Very helpful, if you add a pond, says Associate Professor of Ecology at Northumbria University, Mike Jeffries.

Read more: Ponds can absorb more carbon than woodland – here’s how they can fight climate change in your garden

A pond that’s only a square metre in size could suck as much as 247g of carbon from the air every year. Though small ponds make up a tiny proportion of the UK’s land area – about 0.0006% of it – they punch well above their weight in terms of how much carbon they can bury as sediment.

By digging a pond in your garden, you’d also be inviting some truly unique wildlife. Perhaps most interesting of all according to Jeffries is the tadpole shrimp – thought to be the oldest animal in the world.

Garden ponds can also draw in more familiar creatures, like frogs and toads. Half of all the UK’s ponds were lost during the 20th century, leaving many native amphibians searching for somewhere to live. As climate change threatens to dry up much of these habitats, garden ponds could provide an oasis for struggling species says Becky Thomas, a Senior Teaching Fellow in Ecology at Royal Holloway University.

Frogs and toads need clean ponds in which to breed [but] the fashion of keeping our gardens meticulously neat and tidy is leaving our wildlife with nowhere to hide. Creating a pond can be a fun project – especially with children. Once put in, it will only take a matter of days before something decides to make it their home. It will usually be invertebrates and plants to begin with, but it won’t take long for it to be found by a nearby frog or toad population.

Read more: Make your garden frog friendly – amphibians are in decline thanks to dry ponds

A shared home for humans and wildlife

No matter where you look, you’re likely to find a potentially useful habitat for nature that’s under threat. Professors of Conservation Ecology Brendan Wintle (University of Melbourne) and Sarah Bekessy (RMIT University) say that even very small patches can be invaluable for a particular species.

It may not look like a pristine expanse of Amazon rainforest or an African savannah, but the patch of bush at the end of the street could be one of the only places on the planet that harbour a particular species of endangered animal or plant.

In Australia, our cities are home to, on average, three times as many threatened species per unit area as rural environments. This means urbanisation is one of the most destructive processes for biodiversity.

Read more: The small patch of bush over your back fence might be key to a species’ survival

Moving out of gardens and into the streets, how could our towns and cities be reimagined with more space for nature? Heather Alberro, a PhD Candidate in Political Ecology at Nottingham Trent University, believes that “urban greening” could make the places we live resilient to climate change and ensure a refuge for biodiversity:

Cool those heat waves: a single tree can have the cooling effect of more than ten air conditioning units, all while absorbing carbon. Higher temperatures turn cities into concrete heat traps, but using air conditioning to stay cool takes a lot of electricity, adding more CO₂ to the atmosphere. By contrast, trees shade surfaces that might otherwise absorb heat and cool the air by gathering water on their leaves which evaporates in the sun.

Filter air pollution: plants capture airborne particulates in the wax or cuticles of their leaves. By filling streets with trees, the air can be made safer to breathe.

Increase biodiversity: rooftop gardens and forested terraces can create habitats in new places. Networks of connected habitats – such as wildflower meadows that snake along roadsides – could allow new urban ecosystems to form, populated by species that had previously been squeezed out of the concrete sprawl.

Read more: Urban greening can save species, cool warming cities, and make us happy

If all that sounds good to you then you’re in luck, Alberro says. Urban greening is being taken very seriously by architects, designers and politicians. You may find your neighbourhood growing wilder in the years to come.

The mass greening and rewilding of our cities is no novel or abstract ideal. It is already happening in many urban spaces around the world. The mayor of Paris has ambitious plans to “green” 100 hectares of the city by 2020. London mayor Sadiq Khan hopes to make London the world’s first “National Park City” through mass tree planting and park restoration, greening more than half of the capital by 2050.

If you live outside a major city then perhaps it’s your daily commute that will change first. Thanks to efforts by campaigners and local councils in the UK, roadside verges are being turned into wildflower meadows, with an eight-mile “river of flowers” now hugging a motorway in Rotherham.

According to Olivia Norfolk – a Lecturer in Conservation Ecology at Anglia Ruskin University – bees and butterflies don’t seem to mind the traffic and their numbers have “increased dramatically” where regular mowing has stopped and wildflower meadows have returned on grass verges. She said:

The UK road network spans over 246,000 miles – reducing mowing on the grass verges that surround them to just once a year could save money and create thriving habitats for pollinating insects that return on their own each spring.

Seeing so much colour on land that was once devoid of life can really lift the spirits. Alberro believes this may be the greatest benefit from rewilding – more human happiness. The Japanese call it Shinrin-yoku, or “forest bathing” – the idea that regular immersion in nature is as good as therapy. In the future, people may not have to go too far to get their fix.

Further reading

National parks are beautiful, but austerity and inequality prevent many from enjoying them

Forget environmental doom and gloom – young people draw alternative visions of nature’s future

Jack Marley, Commissioning Editor, The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.