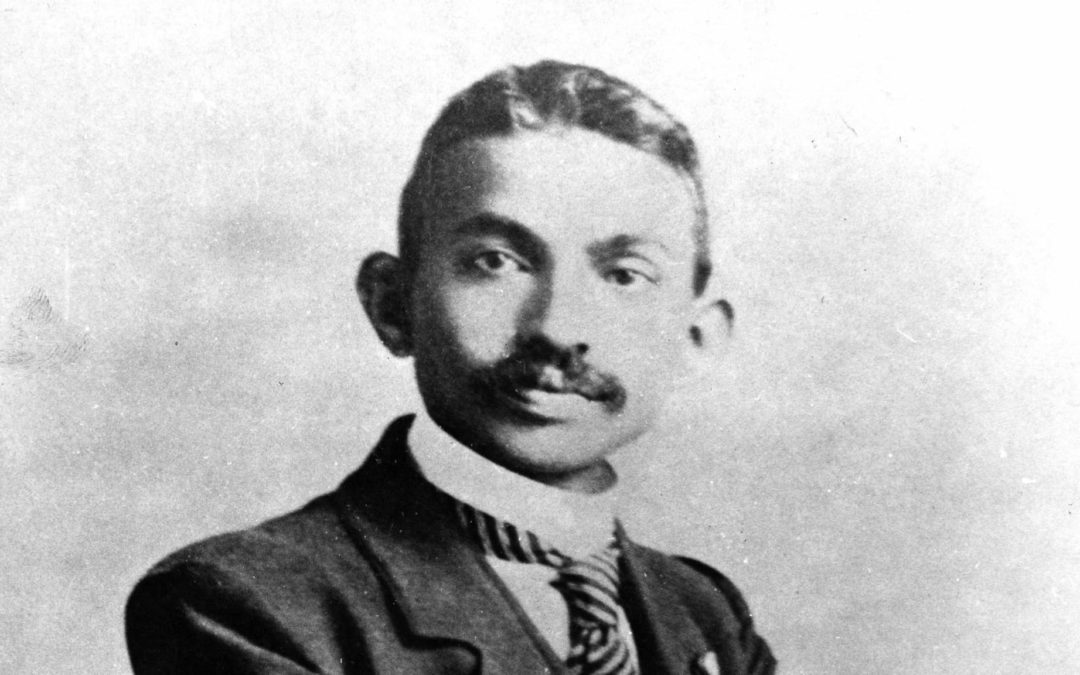

Mahatma Gandhi

The leadership of Mahatma Gandhi has a foundation in self-development. To lead by example, one must first become the type of person that you would like your followers to be. This is achieved through self-sacrifice, understanding, and education.

Rather than justify reasons for contradicting himself, Gandhi would assure his students that whatever he had said second must be correct. The continuous learning that life should include would ensure that his later statement must be more correct. Not only did he believe in ongoing education, but he was willing to admit that he could have been wrong.

Mahatma Gandhi

Gandhi is perhaps most known for accepting people and seeing the best in them. As a leader, there are few characteristics that your followers or employees will find more motivating. Knowing that someone sees the potential in them and has great faith in their abilities often causes people to reach heights that they would not have otherwise. This great faith in humanity is what led to another famous tenant of Gandhi’s: non-violence. When you see the best in all people, you cannot also believe in wanting to harm them.

Discipline

Discipline, even more than great intellect, can help us reach our objectives, according to Mahatma Gandhi. The discipline to be patient, to strive and work, or to accept temporary defeat must all be present in order to lead others. When we lead with emotion rather than discipline, we are much more likely to make decisions that do not optimize long term results.

To a leader like Mahatma Gandhi, how you achieve your results is just as important as the final product. How you treat people and represent yourself throughout your journey should be exemplary or your results are tarnished by the method by which they were reached. Shortcuts and dishonesty can never lead to true success.

As an advocate for peace and human rights, Mahatma Gandhi taught a lesson in effective leadership that continues to be a standard by which many are measured by, 67 years after his death.

What many of us don’t know on the face of things, is that Gandhi was a highly political man, with seminal influence in South Africa around the turn of the 18th century. Born and raised in a Hindu merchant caste family in coastal Gujarat, western India, and trained in law at the Inner Temple, London, Gandhi first employed nonviolent civil disobedience as an expatriate lawyer in South Africa, in the resident Indian community’s struggle for civil rights. After his return to India in 1915, he set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers to protest against excessive land-tax and discrimination. Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, expanding women’s rights, building religious and ethnic amity, ending untouchability, but above all for achieving ‘Swaraj’ or self-rule.

Mandela and the African National Congress

Gandhi, Mandela come together in an art exhibition

Gandhi and John Dube, first President of the African National Congress, were neighbours in Inanda, and each influenced the other, for both men established, at about the same time, two monuments to human development within a stone’s throw of each other, the Ohlange Institute and the Phoenix Settlement.

Both institutions suffer today the trauma of the violence that has overtaken that region; hopefully, both will rise again, phoenix-like, to lead us to undreamed heights.

Prison

During his twenty-one years in South Africa, Gandhi was sentenced to four terms of imprisonment, the first, on January 10, 1908, to two months, the second, on October 7, 1908, to three months, the third, on February 25, also to three months, and the fourth, on November 11, 1913, to nine months hard labour. He actually served seven months and ten days of those sentences. On two occasions, the first and the last, he was released within weeks because the Government of the day, represented by General Smuts, rather than face ‘satyagraha’ and the international opprobrium it was bringing the regime, offered to settle the problems through negotiation.

On all four occasions, Gandhi was arrested in his time and at his [own] insistence – there were no midnight raids, the police did not swoop on him – there were no charges of conspiracy to overthrow the state, of promoting the activities of banned organisations or instigating inter-race violence.

Nelson Mandela

In 1913, Gandhi organised a strike against a £3 tax on people of Indian descent. Through this strike, Gandhi won a victory for Indian civil rights in South Africa. Mishal Husain describes Gandhi’s fight for Indian civil rights in ‘The Making of the Mahatma.’

For the first time he was leading working-class Indians – agricultural labourers and miners. Building on his years of protest, Gandhi decided to lead a march of 2,221 people from Natal into the Transvaal in his final act of public disobedience. Gandhi was arrested and sentenced to nine months imprisonment. But the strike spread and the British were forced to drop the tax and release Gandhi. News of his victory was reported in England and Gandhi started to become an international figure. Here begins the lesson of revolt and uprising against governments in South Africa.

Read more at ‘A comparison of prison experiences and conditions of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela in South Africa by Nelson Mandela’ here.